A new nuclear power station in the south-west of the UK will be the most expensive object on Earth. That's the claim about the proposed plant at Hinkley Point in Somerset - but has anything else ever cost so much to build?

"Hinkley is set to be the most expensive object on Earth… best guesses say Hinkley could pass £24bn ($35bn)," said the environmental charity Greenpeace last month as it launched a petition against the project.

This figure includes an estimate for paying interest on borrowed money, but the financing arrangements for Hinkley C are so opaque that it is impossible to calculate exactly what the final cost will be.

Even if you stick with the expense of construction alone, though, the price is still high - the main contractor, EDF, puts it at £18bn ($26bn). For that sum you could build a small forest of Burj Khalifas - the world's tallest building, in Dubai, cost a piffling £1bn ($1.5bn). You could also knock up more than 70 miles of particle accelerator. The 17-mile-long Large Hadron Collider, built under the border between France and Switzerland to unlock the secrets of the universe, cost a mere £4bn ($5.8bn).

For that sum you could build a small forest of Burj Khalifas - the world's tallest building, in Dubai, cost a piffling £1bn ($1.5bn). You could also knock up more than 70 miles of particle accelerator. The 17-mile-long Large Hadron Collider, built under the border between France and Switzerland to unlock the secrets of the universe, cost a mere £4bn ($5.8bn).

The most expensive bridge ever constructed is the eastern replacement span of the Oakland Bay Bridge in San Francisco, designed to withstand the strongest earthquake seismologists would expect within the next 1,500 years. That cost about £4.5bn ($6.5bn). So why is Hinkley C so expensive?

So why is Hinkley C so expensive?

"Nuclear power plants are the most complicated piece of equipment we make," says Steve Thomas, emeritus professor of energy policy at Greenwich University.

"Cost of nuclear power plants has tended to go up throughout history as accidents happen and we design measures to deal with the risk."

In comparison, the UK's newest nuclear power station, Sizewell B, which was completed in 1995, only cost £2.3bn ($3.4bn), or £4.1bn ($6bn) at today's prices.

No nuclear power plants have been completed in Europe this century - those that have been built in recent years are in countries such as China or India, and Thomas believes figures for these, where they exist, are not reliable.

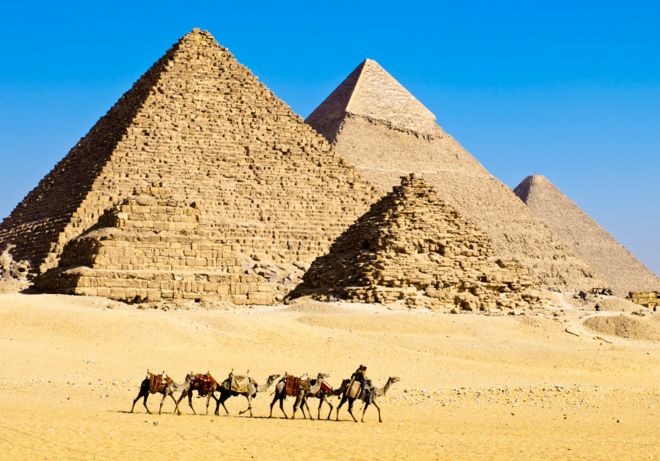

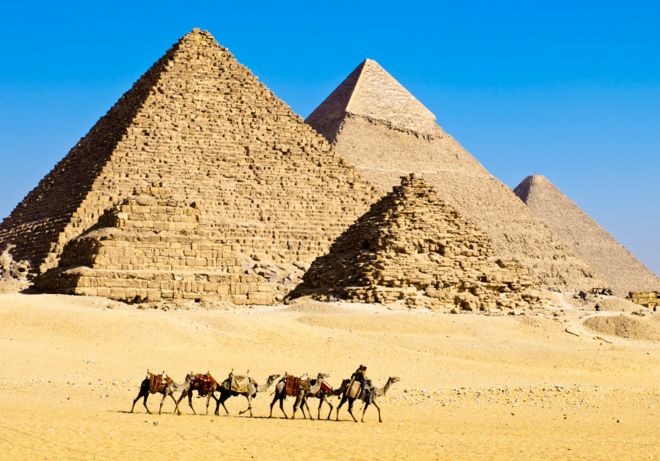

So what about historic buildings - could the Great Pyramid of Giza put Hinkley C in the shade? Working out the cost of something built more than 4,500 years ago presents numerous challenges, but in 2012 the Turner Construction Company estimated it could build the pyramid for between £750m ($1.1bn) and £900m ($1.3bn).

Working out the cost of something built more than 4,500 years ago presents numerous challenges, but in 2012 the Turner Construction Company estimated it could build the pyramid for between £750m ($1.1bn) and £900m ($1.3bn).

That includes about £500m ($730m) for stone and £40m ($58m) for 12 cranes. However, it projected that a mere 600 staff would be necessary - it took 20,000 people to build the original pyramid at a time when the only cranes in sight were the winged, feathery type.

And the cost to Pharaoh Khufu? For two decades, workers are believed to have laboured on the pyramid for four months a year, during the annual Nile flood when the fields they normally tended were submerged. That amounts to 48.4 million days of labour. A further 4,000 people are thought to have worked year-round, giving a total figure of 77.6 million days' labour. Using the current Egyptian minimum wage of £3.93 ($5.73) a day, that gives a labour cost of £305m ($445m).

Using modern labour rates is not as strange as it might seem. A contemporaneous inscription reveals labourers received 10 loaves of bread and a jug of beer per day. Archaeological evidence suggests the pyramid builders also received meat and fish, and in modern Egypt 10 loaves, a can of Coca-Cola and a portion of beef or fish costs about £4 ($5.80).

More or Less is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and the World Service

Download the More or Less podcast

More stories from More or Less And the Pharaoh didn't have to pay for raw materials.

"The king owned all the stone in the quarries," says Joyce Tyldesley, lecturer in Egyptology at Manchester University. "He couldn't sell this - nobody would have a use for it. His palaces and temples were made of mud brick and so were peoples' houses. Nobody would have the resources to buy it. It's a free resource."

She thinks the labour was effectively free too. Workers were paid with food that the pharaoh had gathered in as taxation.

"If he doesn't spend it on his workforce it won't last, he'll have to redistribute it another way," she says. "I would argue the entire pyramid-building experience was free."

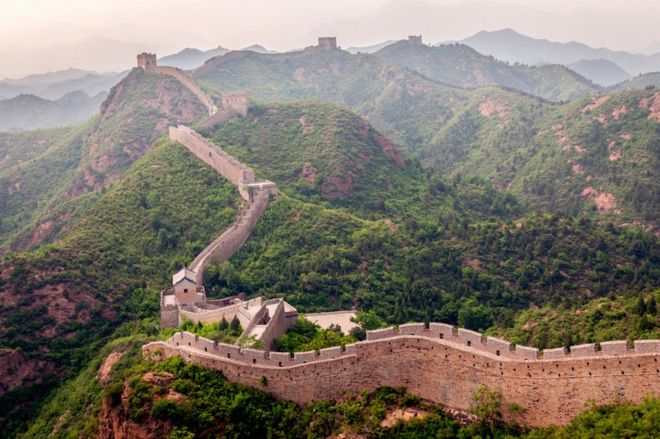

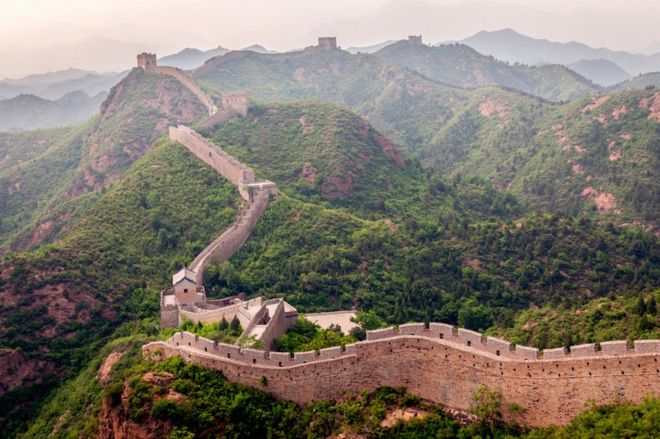

In any case, a £500m stone bill plus £305m in wages are nowhere near Hinkley C. The Great Wall of China was an even bigger project than the pyramid. At 5,500 miles long, its mass is almost certainly greater. But it is actually a large number of walls, pieced together over two millennia, stretching the definition of "object".

The Great Wall of China was an even bigger project than the pyramid. At 5,500 miles long, its mass is almost certainly greater. But it is actually a large number of walls, pieced together over two millennia, stretching the definition of "object".

Back in the modern era, neither Heathrow Terminal 2 (£2.3bn; $3.4bn) nor the new London railway Crossrail (£14.8bn; $21.6bn) can compete with Hinkley.

One current project, at first glance, does appear to be in the same ballpark as the power station. The royal family of Saudi Arabia is refurbishing the Grand Mosque in Mecca at a reported cost of about £16bn ($23bn). But this includes a new road and train line, among other things, so, once again, it stretches the definition of "object". Another contender is Hong Kong International Airport, built in 1998 on an artificial island at a cost of £13.7bn ($20bn) - equivalent to £20.1bn ($29bn) at today's prices. That just pips EDF's estimate for the cost of Hinkley C (though remember, we are putting to one side the cost of financing the deal).

Another contender is Hong Kong International Airport, built in 1998 on an artificial island at a cost of £13.7bn ($20bn) - equivalent to £20.1bn ($29bn) at today's prices. That just pips EDF's estimate for the cost of Hinkley C (though remember, we are putting to one side the cost of financing the deal).

But these are all exceeded by the $54bn (£37bn) Gorgon liquefied natural gas plant built by Chevron in Australia. Built on Barrow Island off the country's north-west coast to process a huge off-shore gas field, it began production in March.

Even that will probably be overtaken one day, though. "We're just building two reactors at Hinkley. Turkey has a deal for four reactors, South Africa is about to launch a tender for six reactors," says Steve Thomas. "When you get round to a six-reactor order it's going to cost three times as much as Hinkley."

And whatever the most expensive object on Earth is, up in the sky is something that eclipses all of these things.

The International Space Station. Price tag: 100bn euros (£77.6bn, or $110bn).

"Hinkley is set to be the most expensive object on Earth… best guesses say Hinkley could pass £24bn ($35bn)," said the environmental charity Greenpeace last month as it launched a petition against the project.

This figure includes an estimate for paying interest on borrowed money, but the financing arrangements for Hinkley C are so opaque that it is impossible to calculate exactly what the final cost will be.

Even if you stick with the expense of construction alone, though, the price is still high - the main contractor, EDF, puts it at £18bn ($26bn).

For that sum you could build a small forest of Burj Khalifas - the world's tallest building, in Dubai, cost a piffling £1bn ($1.5bn). You could also knock up more than 70 miles of particle accelerator. The 17-mile-long Large Hadron Collider, built under the border between France and Switzerland to unlock the secrets of the universe, cost a mere £4bn ($5.8bn).

For that sum you could build a small forest of Burj Khalifas - the world's tallest building, in Dubai, cost a piffling £1bn ($1.5bn). You could also knock up more than 70 miles of particle accelerator. The 17-mile-long Large Hadron Collider, built under the border between France and Switzerland to unlock the secrets of the universe, cost a mere £4bn ($5.8bn).The most expensive bridge ever constructed is the eastern replacement span of the Oakland Bay Bridge in San Francisco, designed to withstand the strongest earthquake seismologists would expect within the next 1,500 years. That cost about £4.5bn ($6.5bn).

So why is Hinkley C so expensive?

So why is Hinkley C so expensive?"Nuclear power plants are the most complicated piece of equipment we make," says Steve Thomas, emeritus professor of energy policy at Greenwich University.

"Cost of nuclear power plants has tended to go up throughout history as accidents happen and we design measures to deal with the risk."

In comparison, the UK's newest nuclear power station, Sizewell B, which was completed in 1995, only cost £2.3bn ($3.4bn), or £4.1bn ($6bn) at today's prices.

No nuclear power plants have been completed in Europe this century - those that have been built in recent years are in countries such as China or India, and Thomas believes figures for these, where they exist, are not reliable.

So what about historic buildings - could the Great Pyramid of Giza put Hinkley C in the shade?

Working out the cost of something built more than 4,500 years ago presents numerous challenges, but in 2012 the Turner Construction Company estimated it could build the pyramid for between £750m ($1.1bn) and £900m ($1.3bn).

Working out the cost of something built more than 4,500 years ago presents numerous challenges, but in 2012 the Turner Construction Company estimated it could build the pyramid for between £750m ($1.1bn) and £900m ($1.3bn).That includes about £500m ($730m) for stone and £40m ($58m) for 12 cranes. However, it projected that a mere 600 staff would be necessary - it took 20,000 people to build the original pyramid at a time when the only cranes in sight were the winged, feathery type.

And the cost to Pharaoh Khufu? For two decades, workers are believed to have laboured on the pyramid for four months a year, during the annual Nile flood when the fields they normally tended were submerged. That amounts to 48.4 million days of labour. A further 4,000 people are thought to have worked year-round, giving a total figure of 77.6 million days' labour. Using the current Egyptian minimum wage of £3.93 ($5.73) a day, that gives a labour cost of £305m ($445m).

Using modern labour rates is not as strange as it might seem. A contemporaneous inscription reveals labourers received 10 loaves of bread and a jug of beer per day. Archaeological evidence suggests the pyramid builders also received meat and fish, and in modern Egypt 10 loaves, a can of Coca-Cola and a portion of beef or fish costs about £4 ($5.80).

More or Less is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and the World Service

Download the More or Less podcast

More stories from More or Less And the Pharaoh didn't have to pay for raw materials.

"The king owned all the stone in the quarries," says Joyce Tyldesley, lecturer in Egyptology at Manchester University. "He couldn't sell this - nobody would have a use for it. His palaces and temples were made of mud brick and so were peoples' houses. Nobody would have the resources to buy it. It's a free resource."

She thinks the labour was effectively free too. Workers were paid with food that the pharaoh had gathered in as taxation.

"If he doesn't spend it on his workforce it won't last, he'll have to redistribute it another way," she says. "I would argue the entire pyramid-building experience was free."

In any case, a £500m stone bill plus £305m in wages are nowhere near Hinkley C.

The Great Wall of China was an even bigger project than the pyramid. At 5,500 miles long, its mass is almost certainly greater. But it is actually a large number of walls, pieced together over two millennia, stretching the definition of "object".

The Great Wall of China was an even bigger project than the pyramid. At 5,500 miles long, its mass is almost certainly greater. But it is actually a large number of walls, pieced together over two millennia, stretching the definition of "object".Back in the modern era, neither Heathrow Terminal 2 (£2.3bn; $3.4bn) nor the new London railway Crossrail (£14.8bn; $21.6bn) can compete with Hinkley.

One current project, at first glance, does appear to be in the same ballpark as the power station. The royal family of Saudi Arabia is refurbishing the Grand Mosque in Mecca at a reported cost of about £16bn ($23bn). But this includes a new road and train line, among other things, so, once again, it stretches the definition of "object".

Another contender is Hong Kong International Airport, built in 1998 on an artificial island at a cost of £13.7bn ($20bn) - equivalent to £20.1bn ($29bn) at today's prices. That just pips EDF's estimate for the cost of Hinkley C (though remember, we are putting to one side the cost of financing the deal).

Another contender is Hong Kong International Airport, built in 1998 on an artificial island at a cost of £13.7bn ($20bn) - equivalent to £20.1bn ($29bn) at today's prices. That just pips EDF's estimate for the cost of Hinkley C (though remember, we are putting to one side the cost of financing the deal).But these are all exceeded by the $54bn (£37bn) Gorgon liquefied natural gas plant built by Chevron in Australia. Built on Barrow Island off the country's north-west coast to process a huge off-shore gas field, it began production in March.

Even that will probably be overtaken one day, though. "We're just building two reactors at Hinkley. Turkey has a deal for four reactors, South Africa is about to launch a tender for six reactors," says Steve Thomas. "When you get round to a six-reactor order it's going to cost three times as much as Hinkley."

And whatever the most expensive object on Earth is, up in the sky is something that eclipses all of these things.

The International Space Station. Price tag: 100bn euros (£77.6bn, or $110bn).

0 Comments