It's the end of the year: time to start fresh, make resolutions and get

ready for 2020.

But as the world counts down to midnight, let's take a moment to

question why people around the planet are celebrating the new year at that very

moment.

It turns out that the new year wasn't always on Jan. 1, and still isn't

in some cultures.

The ancient Mesopotamians celebrated their 12-day-long New Year's

festival of Akitu on the vernal equinox, while the Greeks partied around the

winter solstice, on Dec. 20. The Roman historian Censorius, meanwhile, reported

that the Egyptians celebrated another lap around the sun on July 20, according

to a 1940 article in the journal the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.

During the Roman era, March marked the beginning of

the calendar. Then, in 46 B.C., Julius Caesar created the Julian

calendar, which set the new year when it is celebrated today.

But even Julius Caesar couldn't standardize the

day. New Year's celebrations continued to drift back and forth in the calendar,

even landing on Christmas Day at some points, until Pope Gregory XIII

implemented the Gregorian calendar in 1582. The Gregorian calendar was an attempt to make the calendar

stop wandering with respect to the seasons. Because the Julian calendar had a

few extra leap years than was necessary, by the 1500s, the first day of spring

came 10 days earlier.

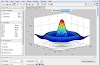

Though the selection of the new year is essentially

arbitrary from a planetary perspective, there is one noteworthy astronomical

event that occurs around this time: The Earth is closest to the sun in

early January, a point known as the perihelion.

Nowadays, Jan. 1 is almost universally recognized

as the beginning of the new year, though there are a few holdouts: Afghanistan,

Ethiopian, Iran, Nepal and Saudi Arabia rely on their own calendrical

conventions.

0 Comments